Voices from the prison

Swedish composer Maria W Horn’s Panoptikon, which she adapted for this year’s Donaufestival in Krems, is based on the first panoptic prison in Sweden. An interview about site-specificity, religion, and surveillance.

Maria W Horn beim Donaufestival | © DavidVisnjic/donaufestival

The panopticon, a prison design conceived by philosopher Jeremy Bentham, allows a single unseen observer to monitor all inmates—an architecture of control that has since become a metaphor for modern surveillance. Swedish composer/artist Maria W Horn has turned this concept into sound. Her piece Panoptikon draws from the history of Sweden’s first panoptic prison, reimagining it as a haunting choral installation. We met at Donaufestival in Krems, where the multi-channel-installation was staged inside the Minoritenkirche.

Bohema/Anton Schroeder: I read that you composed Panoptikon in relation to a specific panoptic prison in Sweden called Vita Duvan. Could you tell me a bit about that place?

Vita Duvan | © Erland Sundström

Maria W Horn: The piece was originally a commission from the Biennale in northern Sweden, in a city called Luleå. It was an open-ended commission—they asked me to find a place, a building, or a site in or around the city as a basis for a new work. I had complete freedom. So, I went there and spent three days doing research—just walking around, visiting different places: sawmills, shoe shops, all kinds of strange locations—trying to imagine what I could do. I knew I wanted to work with multi-channel sound and light, as I had done before. But nothing really clicked—until the third day, when I happened to walk past this very peculiar hexagonal building, kind of circular with a small tower. I asked around and learned that it had once been Sweden’s first panoptic prison. That discovery really struck me, and I began researching it in more depth. The prison has been abandoned for many years. My idea was to place one loudspeaker and one light source in each cell. While researching, I found archival material—prison records in which the prison priest had interviewed inmates and documented their supposed inner transformations. One passage described the Sunday church service, the only time inmates were allowed to open the hatches on their cell doors to hear the priest and sing hymns. They couldn’t see each other; they didn’t even know who the other prisoners were. But for that one moment, they could hear one another and sing together. That image stayed with me, and I decided to base the whole piece on it—imagining a song cycle for those prisoners.

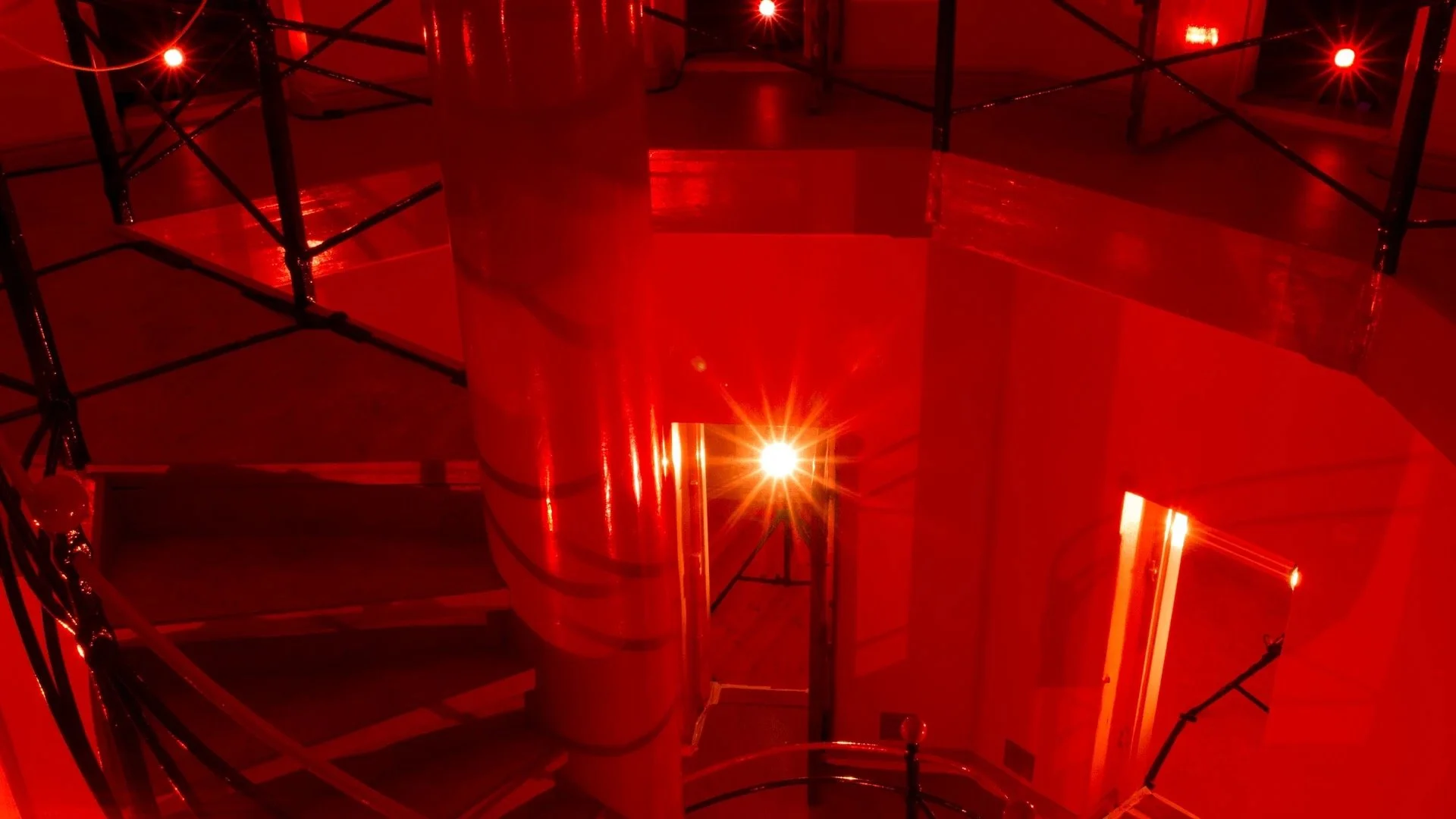

B: So one speaker represents one inmate. I read about that in the festival catalogue —it makes perfect sense when presented inside a prison. But here at Klangraum Krems, in the Minoritenkirche—which obviously isn’t a prison—it feels very different. How did you translate the idea into this space?

MWH: I’ve installed the piece in different locations, and yes, it's always a challenge. Every room carries its own history. Sometimes it's easier to work in a neutral black-box space. But here, or in any space with its own historical weight, it creates a kind of "double exposure." In this case, it worked in an interesting way—partly because of the overlap between the hymns and the building’s monastic history. And of course, Krems itself has this enormous, omnipresent panoptic prison nearby—one of the largest high-security prisons in Austria, maybe even in Europe. That proximity was fascinating to me. Many people here don’t even realize it’s there. So that became a very tangible connection. And yes, that prison is still in use—and still has panoptic architecture.

B: The room in Krems has a central pillar, which almost feels symbolic in relation to the panopticon concept. What I found especially interesting is how the audience is arranged in a circle around the pillar—kind of in-between. The pillar becomes the observer, the speakers are the inmates, and the audience exists in this transitional space.

MWH: Exactly. The room itself is somewhat limited in terms of what you can do. Initially, we made the setup smaller, to keep it circular. But then we had to adapt it to be safe for people to walk around. This version was a good compromise, I think. It’s different from previous iterations—but each space always requires some adaptation.

B: Is that how you usually work? Do you typically start with a space and adapt the piece to it?

MWH: That’s my ideal way of working. I love creating site-specific pieces—composing something for a particular space, room, or instrument. That’s when really interesting things happen—when you can work with the acoustics, the architecture, and the history of a space. I try to do that with many of my commissioned works. But of course, there's always the reality of having to present the work in other venues later. Then you need to adapt again. Sometimes it translates well, sometimes it’s tricky. It's always a balancing act.

Panoptikon at Minoritenkirche, Donaufestival Krems | © Donaufestival Promo

B: You mentioned that the religious aspect of the piece came from the prison history—especially the Sunday services and the singing. Yesterday, when I sat in the installation, I also felt this link between the monastery’s religious atmosphere and the panopticon idea. A kind of omnipresent observer—like a God who sees everything. That can feel either comforting or oppressive.

MWH: Yes, religion can function as a kind of social control system, too. There definitely are parallels. Like I said, idea for the song cycle came from that passage about the priest and the ceremony. I ended up writing my own hymns, but the inspiration was there. Some of them are deconstructed—like the first one, which is built from isolated phrases in a call-and-response structure that gradually builds into all the singers joining in. That layering definitely comes from the idea of communal hymn singing.

B: What are the texts they sing?

MWH: The first hymn uses the phrase Omnia sitra mortem—Latin for “everything except death.” I found it in Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, where he writes about forms of surveillance and punishment. Historically, it has been used to say that anything could be done to someone short of killing them. It's a very brutal phrase. The second hymn is Haec est regula recti, which comes from Rousseau and relates to the correction of children—like the idea of disciplining or "fixing" their deformities. The last piece is a Swedish folk song from the region where the prison is located. It has a very poetic text. I recomposed it slightly. The lyrics say something like: “The forest shall turn into a dove before I see you again, my friend.”

B: How do you think the idea of the panopticon has changed today? It's not just about being watched—but about feeling watched all the time.

MWH: We carry it in our pockets now. (points at her phone) We’ve become so good at controlling ourselves, we don’t even need an external observer anymore. The surveillance has been internalized.

Maria W Horn | © Mats Erlandsson

Förr skall Hällebergen rämna såsom is Förr skall solen bortmista sitt sken

förr skall skogen bli förvandlad till en duva Än jag någonsin dig, min vän återser

The mountain of Hel will crack like ice The sun will lose its shine

The forest will turn into a dove

Before I forsake you, my friend

(from Längtans Vita Duva,

a traditional folk song from Närke used in Panoptikon)